Michi Saagiig History

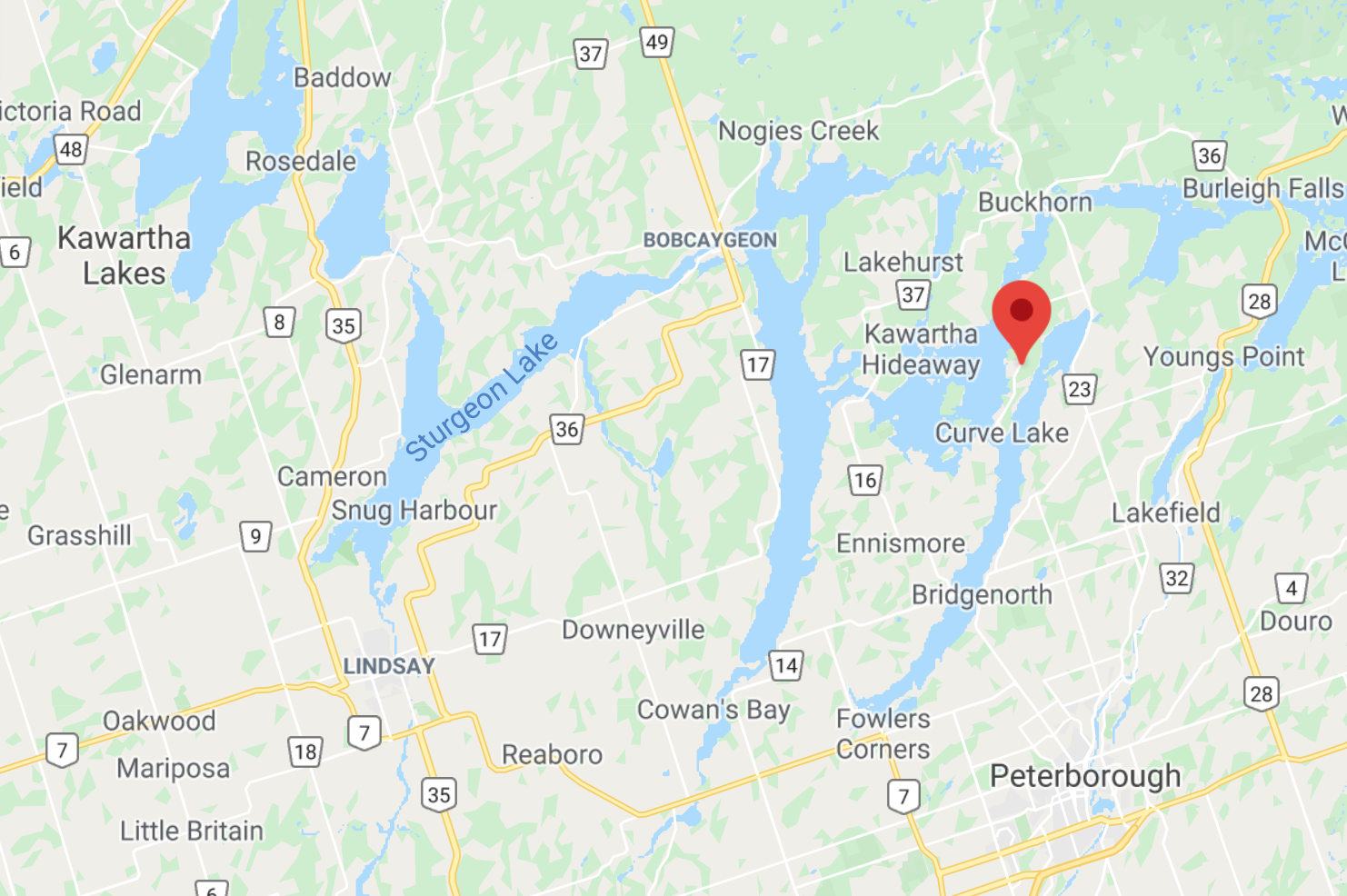

Truth and Reconciliation Community Bobcaygeon is located in the territory of the Michi Saagiig Anishinaabe. Nation-to-nation treaties were signed in 1818 (Treaty 20) and again in 1923 (Williams Treaties) to allow European settlers to live in this area. These treaties are still in effect today.

The closest First Nation community to Bobcaygeon is Curve Lake First Nation. The following information is shared from their website:

“Curve Lake First Nation people are the Mississaugas of the great Anishnaabeg (uhnish-nahbe) nation. The name Anishnaabeg is derived from an-ish-aw, meaning “without cause” or “spontaneous”, and the word in-au-a-we-se, meaning “human-body”. This translates to mean “spontaneous man”. The Anishnaabeg did not have a written alphabet, they did have a set of picture symbols or pictographs which were used to educate through stories. Traditional teachings have taught us that before contact we shared the land with the Odawa and Huron nations. We are the traditional people of the North shore of Lake Ontario and its tributaries; this has been Mississauga territory since time immemorial.” (excerpt from official CLFN website)

Michi Saagiig Historical Context

Excerpt from the Official Background Released by Curve Lake First Nation

“The traditional homelands of the Michi Saagiig (Mississauga Anishinaabeg) encompass a vast area of what is now known as southern Ontario. The Michi Saagiig are known as “the people of the big river mouths” and were also known as the “Salmon people” who occupied and fished the north shore of Lake Ontario where the various tributaries emptied into the lake. Their territories extended north into and beyond the Kawarthas as winter hunting grounds on which they would break off into smaller social groups for the season, hunting and trapping on these lands, then returning to the lakeshore in the spring for the summer months…

Michi Saagiig oral histories speak to their people being in this area of Ontario for thousands of years… The Michi Saagiig of today are the descendants of the ancient peoples who lived in Ontario during the Archaic and Paleo-Indian periods. They are the original inhabitants of southern Ontario, and they are still here today.”

Download the whole story: Michi-Saagii-Territory-history-and-the-Making-of-Canada

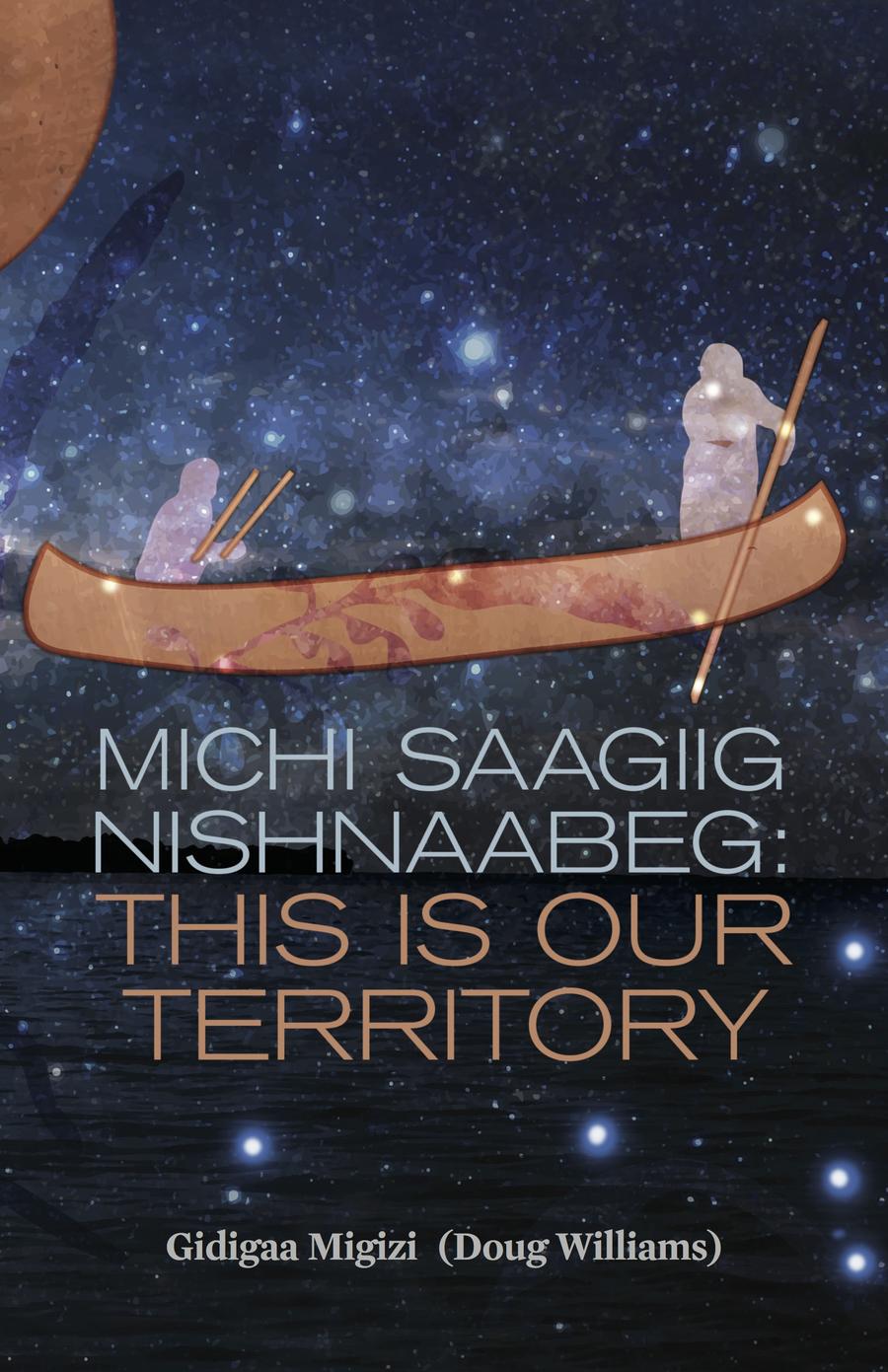

Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg: This is Our Territory

Doug Williams (Gidigaa Migizi-bann)

In this deeply engaging oral history, the late Doug Williams, Anishinaabe elder, teacher and mentor to Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, recounts the history of the Michi Saagiig Nisnaabeg, tracing through personal and historical events, and presenting what manifests as a crucial historical document that confronts entrenched institutional narratives of the history of the region. Edited collaboratively with Simpson, the book uniquely retells pivotal historical events that have been conventionally unchallenged in dominant historical narratives, while presenting a fascinating personal perspective in the singular voice of Williams, whose rare body of knowledge spans back to the 1700s. With this wealth of knowledge, wit and storytelling prowess, Williams recounts key moments of his personal history, connecting them to the larger history of the Anishinaabeg and other Indigenous communities. ~ Description from ARP books

Early Indigenous History in the

Kawarthas

Read the history from our TRC Bobcaygeon pamphlet

At least 12,000 years ago First Peoples migrated into the area we know today as the Kawarthas, soon after the retreat of the great ice sheet. Their arrival has been documented by archaeologists on Rice Lake and Stony Lake near Burleigh Falls. These sites are some of the earliest human habitations found in Ontario.

As the ice sheets and water continued to diminish, about 10,000 years ago, the Kawarthas began to look more like it does today. Forests were abundant with many types of deciduous and coniferous species. These changes in turn increased the animal and fish populations which encouraged Indigenous people to stay longer in one spot and build small communities. Archaeologists have found evidence of habitations throughout the area, including Pigeon, Balsam, Stony and Rice Lakes.

The evidence archaeologists find at these sites is called ‘habitation debris’. This debris could be evidence of manufacturing stone tools and cooked animal bones. Scientists have also found technological innovations like fish weirs at Lovesick Lake. The Kawartha landscape held great spiritual and cultural meaning for the Indigenous populations (as it still does today). Ceremonial and burial sites were used for many hundreds of years. Jacob Island in Pigeon Lake is one of these ‘special’ places and according to Dr. James Conolly, Professor of Archaeology at Trent University, had been used from about 4500 to 1000 years ago.

Another important site available to visitors is the Teaching Rocks, or Petroglyphs near Woodview. Early evidence from about 2500 years ago has been uncovered on Chiminis (Big/Boyd) Island in Pigeon Lake. These sites

emphasized the importance of hunting, trapping, fishing and making use of the wetland resources like Manomin (wild rice). A more complex ceremonial centre from about 2000 years ago can be found at Serpent Mounds on Rice Lake. There are also many more places in the Kawartha Lakes where archaeologists have uncovered marine shells, silver jewelry and musical instruments used in ritual and ceremony.

Indigenous populations began maize cultivation and ‘managed’ landscapes around AD1300. Fields, fruit trees, prairies and mature open forests were tended by local people who have continuously been in the

Kawarthas since the ice receded. The world of Indigenous people changed dramatically when settlers and traders from Europe began to populate North America. Samuel de Champlain came through the Kawarthas in 1615 when he, along with others over time, contributed to escalating regional warfare between Indigenous groups. Battles were fought along the Otonabee River and in the Rice Lake region. Fox Island, Buckhorn Lake was also an important skirmish site. A musket ball has been found on Jacob Island.

By the late seventeenth century the Michi Saagiig (Ojibwa) had successfully pushed back the Iroquois and colonial powers (French, British). They controlled much of southern Ontario and the Kawarthas for the next 100 years. The pressures of increased European and post American Revolution migrations pushed the Indigenous populations into unwanted land treaty negotiations.

Treaty Number 20, 1818, was signed between the Crown and the ‘Principal Men of the Chippewa (Ojibwa) Nation of Indians’. The first legal settlers arrived in the Kawarthas that autumn. Treaty Number 20 meant the surrender of Indigenous land but not the loss of hunting, harvesting and propagation rights to crops like Manoomin.

The international legal concept terra nullius (“nobody’s land”) and the Spanish “Doctrine of Discovery” (1493) ensured that Indigenous peoples around the world were erased as both people and nations for the purposes of European expansion. In order for colonizers to uphold their own rules of law it was necessary to declare the “New World” unoccupied and uninhabited.

In precisely this way, the legal foundation of Canada is built on the premise that Indians do not exist as people. The state has a strong interest in upholding this lie: its legitimacy—its very existence—depends on it. ~ Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

LINKS

Treaties in Michi Saagiig Territory

Ontario Ministry of Indigenous Relations & Reconciliation – TREATIES

Map of Williams Treaties and Pre-Confederation Treaties

Williams Treaty (1923) Research Report